Colonial policies | Freedom Struggle >>

[…] In India, as elsewhere, colonialism is “first, foremost and always” about land. As in North America and Africa, the policing of reserve forests has often resulted in what amounts to ethnic cleansing, with Indigenous peoples being evicted from their homelands for the benefit of the tourism industry and its urban, middle-class clients. Displaced Adivasis are often forced to relocate to settlements that bear a strong resemblance to reservations.

Legal protections for Adivasis were never very strong in India; since colonial times, officially designated forest lands—which cover no less than a fifth of the country’s surface area—have formed an internal “state of exception” where the normal functioning of the laws of the land are suspended. This realm is controlled by the Forest Department (an immense bureaucracy with vast powers) and an army of forest guards that functions like a paramilitary force. This department bears a more than passing resemblance to the settler-colonial bureaucracies that dealt with Indigenous affairs in North America and Australia: like them, it has proved to be an effective instrument in helping corporate interests penetrate deeper and deeper into regions that were once protected by their remoteness. As in North America and Africa, the policing of reserve forests has often resulted in what amounts to ethnic cleansing, with Indigenous peoples being evicted from their homelands for the benefit of the tourism industry and its urban, middle-class clients. Displaced Adivasis are often forced to relocate to settlements that bear a strong resemblance to reservations.

The parallels abound: as with the “Indian boarding schools” of North America, privately owned institutions are now reeducating Adivasi children; in consonance with settler-colonial practice, the material basis of Adivasi life is being steadily undermined by restricting access to traditional foraging grounds and the banning of certain kinds of hunting and gathering. As in the Americas and Australia, mines and extractive industries are being sited on mountains and other locations that are sacred for Adivasis. Completing the parallels are the long-simmering, decades-long “irregular wars,” fought between government forces and tribal insurgents in central, eastern, and northeastern India.

But within this grim and steadily darkening picture, there are also a few points of light, emanating mainly from grassroots resistance movements—and it is no coincidence that some of them exemplify the possibilities of vitalist forms of politics. One of the most notable of these was the Chipko movement of the mountain region of Uttarakhand. […]

Ultimately, as Mukul Sharma notes, the strength of the Indian environmental movement lies in its heterogeneity: “In their practical political activities, many environmental groups and movements have been at the forefront of efforts to democratize state institutions, as well as in the creation of more democratic and accountable forms of environmental decision-making.”

All of this conforms to what appears to be a consistent pattern in the relationship between vitalist ideas and politics: almost always, beliefs in the Earth’s sacredness and the vitality of trees, rivers, and mountains are signs of an authentic commitment to the defense of nonhumans when they are associated with what Ramachandra Guha calls “livelihood environmentalism”—that is to say, movements that are initiated and led by people who are intimately connected with the specificities of particular landscapes. By the same token, such ideas must always be distrusted and discounted when they are espoused by elitist conservationists, avaricious gurus and godmen, right-wing cults, and most of all political parties: in each of these manifestations they are likely to be signs of exactly the kind of “mysticism” that lends itself to co-optation by exclusivist right-wingers and fascists.

Source: “Congress, Left, BJP – India striving to remake itself as settler colonialist: Amitav Ghosh”

URL: https://theprint.in/pageturner/excerpt/congress-left-bjp-india-striving-to-remake-itself-as-settler-colonialist-amitav-ghosh/750429/

Date Visited: 26 October 2021

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

“The practice of religious rituals, ceremonies and sanctions by specific cultural groups allow such sacred landscapes to be maintained, emphasizing that humans are intrinsically part of the ecosystem. Taboos, codes and customs specific to activities and community members restrict access to most sacred groves. […] The inclusion of local people’s needs and interests in conservation planning is increasingly accepted as essential, both to promote the well-being of human populations, and to ensure that biodiversity and conservation needs are met in the long-term.” – Nazir A. Pala, Ajeet K. Neg and N.P. Todaria in “The Religious, Social and Cultural Significance of Forest Landscapes in Uttarakhand Himalaya, India” (International Journal of Conservation Science, Vol. 5, Issue 2, April-June 2014) | Sacred groves | Biodiversity and development – Himalaya >>

Find articles by Mukul Sharma (Ashoka University, Dept. of Environmental Studies) on Academia.edu >>

Tips for using interactive maps

Toggle to normal view (from reader view) should the interactive map not be displayed by your tablet, smartphone or pc browser

For details and hyperlinks click on the rectangular button (left on the map’s header)

Scroll and click on one of the markers for information of special interest

Explore India’s tribal cultural heritage with the help of another interactive map >>

See also

Adverse inclusion | Casteism | Rural poverty

Demographic Status of Scheduled Tribe Population of India (Census figures 2011)

Fact checking | Figures, census and other statistics

Human Rights Commission (posts) | www.nhrc.nic.in (Government of India)

Search tips | Names of tribal communities, regions and states of India

“What is the Forest Rights Act about?” – Campaign for Survival and Dignity

“Who are Scheduled Tribes?” – Government of India (National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, NCST)

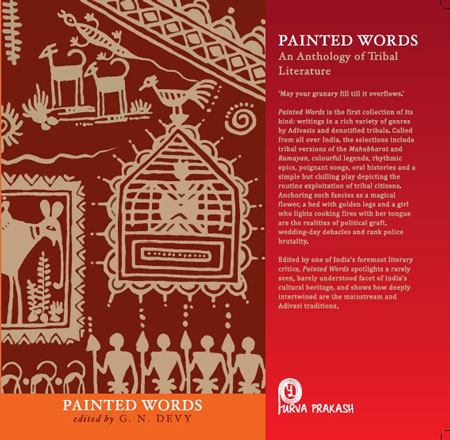

Tribal Literature by G.N. Devy >>

Free eBooks & Magazine: Adivasi literature and languages >>

“India, a union of states, is a Sovereign, Secular, Democratic Republic with a Parliamentary system of Government. The President is the constitutional head of Executive of the Union. In the states, the Governor, as the representative of the President, is the head of Executive. The system of government in states closely resembles that of the Union. There are 28 states and 8 Union territories in the country. Union Territories are administered by the President through an Administrator appointed by him/her. From the largest to the smallest, each State/UT of India has a unique demography, history and culture, dress, festivals, language etc. This section introduces you to the various States/UTs in the Country and urges you to explore their magnificent uniqueness…” – KnowIndia (Government), States and Union Territories (Visited: 2 September 2023)

Learn more about India’s 28 States and 8 Union Territories – From Andhra Pradesh to West Bengal | Nutrition >>

See also

Education and literacy | Right to education

Freedom of the press | World Press Freedom Index

Journalism | Find press reports on India’s tribal heritage and democracy: Journalism without Fear or Favour, The Committee to Protect Journalists & United Nations

People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)

Proper coverage of “deprivation”: Ethical considerations for students of Indian journalism

Recovering tribal culture from the misrepresentation of mainstream media