[N]ew pedagogic practices require to be evolved in order to execute various developmental programmes. In doing so, good practices that exist in the society may turn out to be very handy. In case of tribal societies, for example, there are two striking aspects with regard to caring for the child and nurturing the young. One is the prevalence of breast feeding and the other is the tradition of kin/community care of the children. It is the kin care that explains as to why it is rare to find destitution and begging among tribal population, including tribal children. Equally important in this respect is the emphasis on ethics of work, which the children internalise quite early in life. Things have however begun to change because of displacement due to development projects and lack of rehabilitation and resettlement of displaced population.

Source: Virginius Xaxa in The Status of Tribal Children in India: A historical perspective, IHD – UNICEF Working Paper No. 7 “Children of India: Rights and Opportunities”, Institute for Human Development, United Nations Children’s Fund, India, 2011

URL: https://www.ihdindia.org/pdf/virginius_xaxa.pdf

Date Visited: 27 May 2022

“Tribal children have higher levels of undernutrition compared to children of socially economically advanced sections.” | Learn more >>

On May 29 and 30, Vidya Vanam [about 30 km from Coimbatore, on the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border] will host a National Conference and Workshop on Educating for a Caring Society. The presentations in the morning will be followed by workshops on how these ideas can be incorporated in the classrooms. Rangachary plans to get teachers from mainstream schools to attend. She said, “Some of these ideas are already there in institutions like Shantiniketan and KFI [Krishnamurti Foundation India], but these are alternative schools. How do we bring these ideas to the fore, and say that these are not just for a small group of people but for the school system at large? Education has become impersonal and fear-ridden. It should be something that’s enjoyed by both teachers and students.” […]

The students at Vidya Vanam — most of them first-generation learners — are from the Irula tribe, the Adi Dravidar communities, and the BC, MBC and OBC categories. They are here because their parents, who are mostly daily wage earners, want them to learn English. [Prema] Rangachary [the 71-year-old director of Vidya Vanam], who is from Chennai, first came to Anaikatti in 2001, when a friend asked her to help out with anganwadis in remote villages in the forest areas. There, she met parents such as Valli, whose child studies in Vidya Vanam today. Valli asked her, “Why don’t you start a school?” There were others too. Rangachary remembers what they told her. “Neenga pesara maadhiri avanga English pesanum.” They wanted their children to speak English the way she did, but they could not afford an English-medium school.

As it turned out, many of them could not afford any kind of education. When the idea of a school began to take root — thanks to contributions from Rangachary’s brother, a neurologist in the US who helped set up a foundation, and Swami Dayananda Saraswati, who donated the land — Rangachary called the headmen of the villages and asked them how much they could give as fees. After a brief discussion, they said they could give a day’s wage: Rs. 150 per child each month. But this has not always been possible. Next year, Rangachary plans to make schooling free for tribal children. […]

Vidya Vanam was inaugurated in July 2007. Twenty children, aged three-and-a-half to eight, came on the first day. By the end of the month, the number doubled. Today, there are 270 students, in classes named after fruits (Orange, Mango), trees (Neem, Pipal, Jamun, Banyan), and rivers (Kaveri, Bhavani, Krishna, Alakananda, Ganga). […]

There are no marks or grades till Ganga class. There are only evaluations for the teacher to understand where the student is. I looked at some of the report cards. One of these evaluations said, “Vishnu is regular in doing his assignment.” Another one said, “Plays only with friends”.

There are no prescribed textbooks either. The teachers cull material from books and distribute photocopies to students. And the lesson plans are based on interdisciplinary interactions around the same theme. If the theme is water, then the Science class will talk about two molecules of Hydrogen and one of Oxygen, the History class will get into civilisations that flourished along rivers, and Maths class will calculate the volume of a dam. They even staged a dance drama based on the Cauvery. Rangachary said that there was a constant endeavour to keep the children connected to their surroundings. They once went to a nearby village to study the flora and fauna, the community, and the river that flowed through it. “They need to know these rivers before they study about the Nile and the Amazon,” Rangachary said. I had to keep reminding myself that this isn’t an upscale, newfangled facility with avant-garde notions of education but a school for tribal and underprivileged children.

Rangachary doesn’t hesitate to call Vidya Vanam an experiment. “In a rural setup like this, I have a free environment,” she said. “It is not very structured.” The parents did not accept this the first two years. “Even though they were not educated, even though they could not help their child in any manner, they wondered what we were doing here, what their children were learning, whether the child would get a certificate. But they were convinced once they saw the changes in their children.” It helped that the teachers, at first, were from the same villages as these parents. “That increased their comfort level with the school. Now, we even have foreign teachers.” […]

Rangachary told me that schooling is bilingual — Tamil and English — till the children are about eight, and later classes are conducted more in English. While there are many teachers who are locals (even if it does seem a stretch to call Srividhya akka, who travels 45 km to get here, a local), the teachers from outside — outside the state, outside the country — are a logical extension of the parents’ original mandate to teach their children English. I spoke to Sivammal, whose three children are students at Vidya Vanam. She said that she liked Vidya Vanam because they teach Hindi here. When her husband, a welder, went to Delhi on work, he didn’t understand a word there. She said, “At least my kids will have a good future.” […]

Some of this free-style experimentation with mixed-age, mixed-ability classes may soon come to an end. Rangachary told me, “We are streamlining the senior classes age-wise because we want the children to be eligible for public exams three years hence.” […]

I asked if learning English could end up changing the dynamics in these households or even alienate the children from their parents. “No,” she said. “The simple reason is that it’s these parents who asked for it in the first place. When these children come here, they have no confidence, no sense of self-worth or self-esteem. But after a while, you have to see how much they are respected in their own environment.” From next year, Vidya Vanam plans to have a vocational stream as well. “These children should not think that the next step has to be a BA or an MA in a faraway college. They can also be an entrepreneur and earn a living in their village.” […]

“But I think we need to give them the freedom of learning up to Class VII. Today, they are not afraid of expressing themselves. I need that self-confidence in them before they can take an exam, and that has been built up over the years.” I asked her how she thought her students would fare in the board exams. “Of course they will succeed,” she said. After a pause, she added, “We may not have state rankers but we will definitely do very well.”

Source: “The school in the forest” by BARADWAJ RANGAN, The Hindu, SUNDAY MAGAZINE, 24 May 2014

Address : http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/the-school-in-the-forest/article6044227.ece

Date Visited: Tue May 27 2014 14:14:16 GMT+0200 (CEST)

Tips for using interactive maps

Toggle to normal view (from reader view) should the interactive map not be displayed by your tablet, smartphone or pc browser

For details and hyperlinks click on the rectangular button (left on the map’s header)

Scroll and click on one of the markers for information of special interest

Explore India’s tribal cultural heritage with the help of another interactive map >>

See also

Adverse inclusion | Casteism | Rural poverty

Demographic Status of Scheduled Tribe Population of India (Census figures 2011)

Fact checking | Figures, census and other statistics

Human Rights Commission (posts) | www.nhrc.nic.in (Government of India)

Search tips | Names of tribal communities, regions and states of India

“What is the Forest Rights Act about?” – Campaign for Survival and Dignity

“Who are Scheduled Tribes?” – Government of India (National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, NCST)

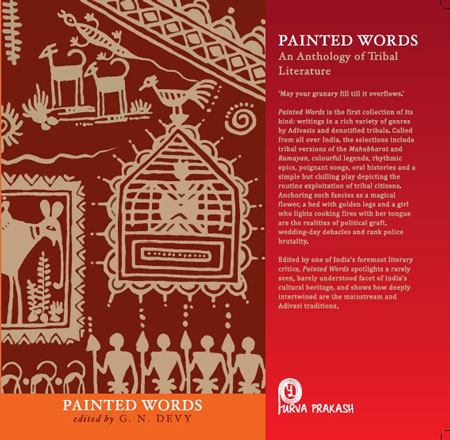

Tribal Literature by G.N. Devy >>

Free eBooks & Magazine: Adivasi literature and languages >>

“India, a union of states, is a Sovereign, Secular, Democratic Republic with a Parliamentary system of Government. The President is the constitutional head of Executive of the Union. In the states, the Governor, as the representative of the President, is the head of Executive. The system of government in states closely resembles that of the Union. There are 28 states and 8 Union territories in the country. Union Territories are administered by the President through an Administrator appointed by him/her. From the largest to the smallest, each State/UT of India has a unique demography, history and culture, dress, festivals, language etc. This section introduces you to the various States/UTs in the Country and urges you to explore their magnificent uniqueness…” – KnowIndia (Government), States and Union Territories (Visited: 2 September 2023)

Learn more about India’s 28 States and 8 Union Territories – From Andhra Pradesh to West Bengal | Nutrition >>

Learn more

Bhasha | Free eBooks & Magazine: Adivasi literature and languages

Books on tribal culture and related resources

Childhood | Childrens rights: UNICEF India | Safe search

Daricha Foundation | Daricha YouTube channel

eBook | Background guide for education

The Food Book of four communities in the Nilgiri mountains: Gudalur Valley – Tamil Nadu

Misconceptions | “Casteism” and its effect on tribal communities

Multilingual education is a pillar of intergenerational learning – Unesco