[…] Fresh from the book launch of Ijlal Majeed’s stunning new poetry collection in Bhopal, I find myself gazing at the rock shelters of Bhimbetka and murmuring these verses over and over again. For indeed there is something subliminal about this place; it makes you question accepted notions of time and timelessness. Looking at the ochre and fire-engine red paintings drawn by human hands several thousand years ago, spotting a buffalo here or a deer there, espying a scene of grief and another of happiness, seeing how our earliest ancestors fought, sang and played makes Bhimbetka a singularly unusual place.

An archaeologist, Vishnu Shridhar Wakankar, chanced upon these rock shelters in 1957 while travelling by train to Bhopal. Hidden by a dense, almost impenetrable, forest inhabited by wild animals, these shelters had long existed in aboriginal folklore and found mention in the popular culture of the Adivasis. With the advent of the Buddhist era, some stupas too came to be built in the vicinity and, though still unexplored, the region became associated with Buddhist lore. The name Bhimbetka, however, is associated with Bhima, the warrior-prince from the Mahabharata known for his immense strength. The word ‘Bhimbetka’ is said to be derived from Bhimbaithka, meaning the baithak (a sit-down) of Bhima. Wakankar’s serendipitous discovery brought the 700-odd rock shelters — spread over 10 km — and the stunning paintings in red or white with the occasional flash of yellow or green to world attention, causing UNESCO to declare them a World Heritage Site in 1970.

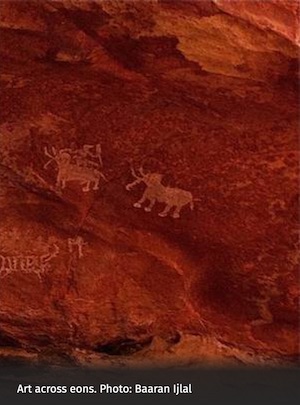

Situated 45 km from Bhopal, at the southern edge of the low-lying Vindhyachal hills, these rock shelters comprise precariously balanced massive sandstone rocks forming natural shelters from the sun, wind and rain. On the smooth underside of the rock faces are painted scenes from an ancient past showing the earliest traces of human life in India. Scientists believe that these rock shelters, deep in the forested heart of the Indian sub-continent, were inhabited by hominids such as Homo erectus more than 100,000 years ago. The rock paintings found here are approximately 30,000 years old, i.e. belonging to the Palaeolithic Age. A cluster of rock shelters, called the ‘Zoo’, shows a profusion of animals and birds in the most vivid colours and lifelike forms. Also the most densely painted, the scenes painted here span from the Mesolithic to the mediaeval: boars, elephants, rhinoceros, barasingha, spotted deer, cattle, snake account for its well-deserved name.

Elsewhere, scenes depicting hunting, fishing and food-gathering as well as communal dances, childbirth, the use of musical instruments, drinking, funerals and burials make these rock surfaces come alive with a thousand stories. Recognisable animals like boar, elephants, buffalo, deer, bison, dog, and monkey appear in many scenes as do humans — both alone and in groups — thus indicating that the concept of a society that had already emerged in the Palaeolithic period. The Mesolithic Age that began nearly 8,000 years before Christ — understood to be the transitional age between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Ages — was the time when traditions and religious beliefs based on nature and ecology began to take shape. The Bhimbetka paintings bear witness to how a great civilisation came into being, how its foundations were laid in crude line drawings and how later generations filled these outlines with colour, detail, a sharp eye and a lively imagination. […]

As the eye travels upwards the scenes are remarkable for their detailing: a spotted deer, a gaily decorated horse, a man carrying a plumed hand-held insignia similar to the ones still used by Adivasi dancers, horse-borne riders carrying blunt stone instruments and then, progressively, bows and arrows, and massed figures engaged in battle. […]

But nothing and nobody could take away the awe we carried home with us — awe in the primeval being that is the Homo sapien, an awe that still makes me break out in goose bumps as I visualise Bhimbetka in my mind’s eye.

Source: “Rocks of ages” by Rakshanda Jalil, The Hindu, 31 August 2013

Address: https://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/rocks-of-ages/article5075148.ece

Date Visited: 7 October 2021

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

See also

Adverse inclusion | Casteism | Rural poverty

Demographic Status of Scheduled Tribe Population of India (Census figures 2011)

Fact checking | Figures, census and other statistics

Human Rights Commission (posts) | www.nhrc.nic.in (Government of India)

Search tips | Names of tribal communities, regions and states of India

“What is the Forest Rights Act about?” – Campaign for Survival and Dignity

“Who are Scheduled Tribes?” – Government of India (National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, NCST)

View Tribal culture in the Indian press in a larger map

Learn more

Crafts and visual arts | Fashion and design | Masks

eBooks, eJournals & reports | eLearning

eBook | Background guide for education

Forest dwellers in early India – myths and ecology in historical perspective

Himalayan region: Biodiversity & Water

History | Hunter-gatherers | Indus Valley | Megalithic culture | Rock art

Languages and linguistic heritage

Modernity | Revival of traditions

Tribal Research and Training Institutes with Ethnographic museums