“They were unable to maintain the city; resources were scarce” – Anindya Sarkar in his article on Dholavira, “the fifth largest site of the Indus Valley Civilization” yet lesser known, asking “Why?”

Learn more

[…] Dholavira is the fifth largest site of the Indus Valley Civilization. It is also the largest excavated site in India? Yet it is lesser known than say, Kalibangan. Why?

I do not know if such a comparison can be made. Kalibangan is located at southern bank of the presently dried river Ghaggar in Rajasthan and characterised by its unique fire altars and one of the world’s earliest ploughed field. But the features of Kalibangan and Dholavira are similar, similar town planning like citadel, lower town etc., and roads which had precision width. The timing is also almost similar from 3500 BCE to 1700 BCE after which both the cities collapsed. The only thing about Kalibangan is it was dated very extensively by archaeologists and its different phases were very well constrained by carbon dating. But after our work, Dholavira archaeological periods are also now on very strong ground in terms of its chronology. Dholavira is lesser known probably due to its remote location in the salt desert and also it was not studied until recently by using modern scientific techniques. In any case both were unique Harappan metropolis exhibiting very advanced city planning not found even in its counterparts in West Asia.

What caused the demise of Dholavira?

From the Later part of Mature Harappan time, i.e. from ~2400 year BCE the expansion of the city at Dholavira slowed down or even ceased until 2300 year BCE with an abrupt decline between 2300 and 2000 year BCE manifested by degeneration of architecture, craftsmanship, and material culture. They were unable to maintain the city; resources were scarce and water reservoirs were no longer in use. Also the site was deserted for few centuries. During the last Stage the city had disappeared, along with the classical Harappan elements and what remained had no resemblance to the Harappan culture. In a sense, it was an attempt to resettle at Dholavira but in a very basic way when probably the pastoralism re‐appeared who had no connection with the developed Harappan culture. Even this was for a very short period and the site was finally deserted. We feel the demise was connected to climate change. We analysed high resolution oxygen isotopes in mollusc shells Terebralia palustris. These are found aplenty in Dholavira, many of them are finely cut by human and were being consumed for food by the Dholavirans. These molluscs typically grow in mangrove suggesting that the people were harvesting them from nearby mangroves. The isotopes tell about the sources and the seasonality of water in which these animals grew. Surprisingly when we analysed the Early to Mature Harappan molluscs (2700 year BCE old) it looked that they grew in a water that is only possible if glacial meltwater mixes in the mangrove. The seasonality was high. This clearly suggested that a glacier fed river was debouching in the Rann of Kutch. But then isotopes in the molluscs from terminal part of mature to late Harappan from 2300 to 2100 years BCE indicated that the glacial contribution disappeared and seasonality reduced. This is the time that exactly coincides with the decadence and fall of the city of Dholavira as indicated by the archaeological evidence and the onset of the newly proposed Meghalayan stage (a divison of geological time) suggested last year by an international body of geologists and stratigraphers when a drought occurred across the globe. We could immediately make the connection. The monsoon was anyway declining. Dholavirans adopted excellent water conservation strategy by building dams, reservoirs and pipelines. But came the apocalypse of few centuries of Meghalayan drought and the whole city collapsed. The collapse of Harappan Dholavira was near‐synchronous to the decline at all the Harappan sites in India like Kalibangan, Lothal, Rakhigarhi as well as Mesopotamia, and the Old Kingdom of Egypt and China.

Your paper says, Dholavira presents a classic case for understanding how climate change can increase future drought risk across much of the sub‐tropics and mid‐latitudes? […]

The final blow to the Harappans, however, came when a global mega‐drought spread over over 2‐3 centuries hit them and they could no longer cope up. And as I said it was collapse of all the major ancient cityscapes across the globe. This seems like a fiction but it teaches us two important lessons. One is we must learn quickly how to cope up with the reduced monsoon and water deficit due to climate change specially our agriculture. Second if we do not learn then a catastrophe is waiting for us. The Dholavirans sustained for 1700 years and the modern civilisation is just about 200 years (if you consider industrial revolution). It is hard to tell what will happen after another 1500 years‐ will mankind survive or perish? […]

*

Anindya Sarkar, professor of geology and isotope geochemistry at IIT, Kharagpur, was lead researcher of a recent paper published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, on how Dholavira, an Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) site, holds important lessons for dealing with climate change. The site was excavated by RS Bisht in the 1990s. Sarkar explains his study to Avijit Ghosh | Read the full interview in the Times of India here >>

Source: ‘Dholavira is the most spectacular Indus Valley site in India; its demise was connected to climate change’

URL: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/Addictions/dholavira-is-the-most-spectacular-indus-valley-site-in-india-its-demise-was-connected-to-climate-change/

Date visited: 27 April 2020

“We face an increasingly unknown world: a changing climate regime and shrinking of the biosphere unlike anything any human community has experienced since the dawn of humanity” – Usha Alexander in “The Overshoot Story: India’s approach to global warming cannot mirror the West” | Read the full article in The Caravan (31 May 2023) >>

Learn more

By USHA ALEXANDER

[…] We must reckon with the underlying reality that our mounting harms to natural systems have thrust us into a condition of ecological overshoot. This means we are depleting essential resources—perhaps most alarmingly, healthy soils—by annihilating living systems, extracting resources and producing pollution at a rate faster than planetary systems can replenish themselves, faster than natural geochemical cycles can restabilise themselves or the beleaguered biosphere can regain its integrity. Humanity’s rate of environmental despoliation has already exceeded at least six of nine known biophysical limits to our planet’s stabilising systems. Only one of these systems is the climate.

Carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases that drive global warming, and the associated particulate matter that clogs and destroys our lungs—as well as, no doubt, the lungs of other animals—are only two types of pollution that industrial consumerist lifestyles generate. There is also the massive chemical runoff from intensive farming, including artificial fertilisers and pesticides, which cause disastrous harm to soil, insects and water bodies. Pollution, acidification and overfishing of the oceans damage marine life. Industrial effluents poison lands and waterways. Meanwhile, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—also called “forever chemicals”—and microplastics have become so pervasive in the environment that every person and other living being is constantly eating, drinking and breathing them in, likely contributing to the present epidemic of infertility, among other health concerns. Light pollution disrupts the nocturnal cycles of plants and animals. […]

Meanwhile, most of us continue to envision a future in which we commute to our jobs and send our children to school to prepare them for the kinds of work we do in an economy similar to the one that presently employs us. This is in denial of the fact that the planet around us is fundamentally changing. In truth, we face an increasingly unknown world: a changing climate regime and shrinking of the biosphere unlike anything any human community has experienced since the dawn of humanity. It is a fact so startling that it hovers beyond our imaginations, even as it engulfs us in real time. Meeting our moment in history will require us all to engage in broader imaginative exercises. It is this that Ashish Kothari and KJ Joy have attempted in Alternative Futures. […]

USHA ALEXANDER trained in science and anthropology. After working for years in Silicon Valley, she now lives in Gurugram. She’s written two novels: The Legend of Virinara and Only the Eyes Are Mine.

Indigenous people represent only about six percent of the world’s population, but they inhabit around a quarter of the world’s land surface. And they share these regions with a hugely disproportionate array of plant and animal life. According to the UN and the World Bank, about 80 percent of our planet’s biodiversity is on land where indigenous people live.

“There is a need to explore the tribal consciousness in the backdrop of climate change, development, and deforestation.” – Deepanwita Gita Niyogi in “India’s Adivasi Identity in Crisis” Pulitzer Center May 27, 2021 | Learn more about climate change and illegal mining | United Nations on climate change | Find free publications on India’s hunter-gatherers in the Unesco Digital Library >>

What is caused (and not caused) by climate change?

How data can help fight a growing tendency by politicians and journalists to overstate the role of climate change| Learn more or listen here >>

linked to each other.” – Droupadi Murmu | Speeches by the 15th President of India >>

Images © publishers, artists & photographers featured by Google Safe Search

Learn more about water-related issues that affect India’s tribal communities >>

“Together, we must endeavour to strengthen tribal communities which are the role model in preservation of water, forest and land, and learn from their connection with nature and the surrounding environment for the sake of the entire human race.” – journalist and tribal rights activist Dayamani Barla in The Wire >>

How much does biodiversity matter to climate change? The ecosystems of the land and ocean absorb around half our our planet warming emissions. But these are being destroyed by human activity. At the same time, climate change is a primary driver of the destruction of these habitats and biodiversity loss. If biodiversity is our strongest natural defence against climate change (as it’s been described), what’s stopping us from doing more to protect it? | For up-to-date reports listen to The Climate Question (BBC) | United Nations on climate change >>

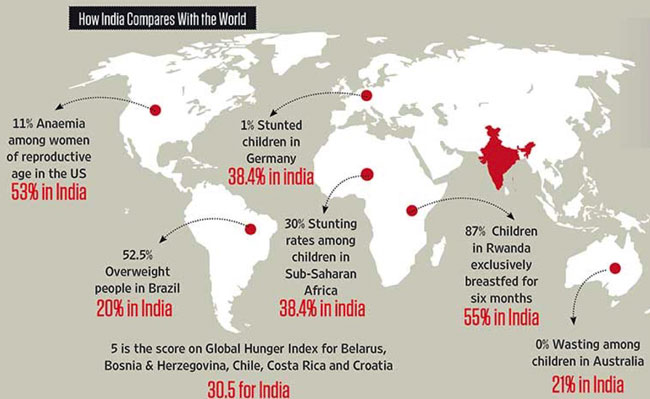

Graphic © Outlook India 26 August 2019 | Enlarge >>

“The tribal food basket has always been diverse and nutritious” >>

“Health spending by the Indian government as percentage of GDP has long been one of the lowest for any major country, and the public health system is chronically dismal.” – Pranab Bardhan in “The two largest democracies in the world are the sickest now” | Learn more: Scroll.in, 24 August 2020 >>

Find publications by reputed authors (add “open access” for freely downloadable content)

PDF-repository: texts quoted & further reference (Google Drive) >>

Learn more

Anthropology | Irish Journal of Anthropology | Folio Special issue

Colonial policies | History | Indus Valley | Mohenjo Daro

eBooks, eJournals & reports | eLearning

eBook | Background guide for education

Ekalavya (Eklavya)

Forest Rights Act (FRA) | Hunter-gatherers | Nishad (Nishada, Sanskrit Niṣāda, “tribal, hunter, mountaineer, degraded person outcast”) | Vanavasi (Vanvasi, Vanyajati)

India’s Constitutional obligation to respect their cultural traditions

Jawaharlal Nehru’s “five principles” for the policy to be pursued vis-a-vis the tribals

Particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG)

Rabindranath Tagore: a universal voice – Unesco

Remembering Birsa Munda: The charismatic tribal leader who shook the British Empire – Jharkhand

Scheduled Tribes | Classifications in different states

Video | Adivasi Academy & Museum of Adivasi Voice at Tejgadh – Gujarat

Video | Tribes in Transition-III: “Indigenous Cultures in the Digital Era”

What is the Forest Rights Act about?

Who is a forest dweller under this law, and who gets rights?