Reams have been written about adivasis by so-called experts. Much of it is subjective interpretation, an exercise I have always been wary of indulging in. For this issue, therefore, my husband Stan and I recorded reflections of different adivasis on how they view life, their religion, politics, the past, the present and the world around them. This then is what the adivasis themselves had to say.

Govinda, a Mullakurumba elder from Onimoola hamlet, Erumadu village began! “Thirty years ago we had hundreds of cattle. There was enough manure to cultivate as much as we needed. Only after all the land has gone do we understand the value of it. We used to hunt every week. We were good archers. Now we sit at home even for Uchchar, our biggest hunting festival. We used to make a kutty bow even for the tiniest baby in the village. He had to hold this for Uchchar. When we had land life was better. Now everyone has more money because they work as labourers. But that cannot last you till you die. It’s only for the able-bodied, only as long as you can go for work.” […]

We never use “English vallam“. Our people can taste the difference in the rice grown with “chanagam” (cowdung) and the other rice. We feel eating rice grown with “English vallam” brings illnesses. For us whatever we get from the land is enough. Our people were never greedy. We could have claimed the entire hillside where we live. We didn’t. Now we’re hemmed in by outsiders.”

Chathi, a Paniya tribal leader from Kayunni grinned, “We say whatever we get is enough. But our non-tribal neighbours say whatever they get is not enough.” Chathi who 10 years ago had never been out of his Nilgiris district has been to Germany and back. Not for him an NRI existence though!

“Life in Germany is good for the Germans,” he announced wisely. “But for me, my village is enough. Germany was nice, but it is like a dream. When you wake up after a dream you remember the nice parts but you do not expect to get all that you saw in the dream. What use is money? I know people who have gone to Dubai and come back rich. But a man must live among his people, his community, his gods. If I cannot see these hills, these paddy fields, hear our adivasi children laugh, hear our music and dance for our festivals, I would pine, grow sick and die.”

Shanthi, a Paniya school teacher was also invited to Germany. “My father and the old people used to talk about the importance of preserving our culture etc. But for me these were only words. When we went to Germany thousands of people were willing to listen to our stories, our music, to come and watch our dancing. I realised the importance of sharing which we take for granted in our adivasi society. People there who had lost their sense of community and sharing envied us. Only then I realised how all this could slip away if we don’t hold on to it. Leaving home made us value our simple life much more.”

Ammani, a Paniya woman leader is typical of her tribe. Strong and forthright, she told us a story of how she solved a family problem. “My husband is very supportive and a good man. But he got into drinking. It is something I wouldn’t tolerate. We had decided in the Sangam to fight alcohol. […]

“There are new differences emerging. Earlier every family in the village was more or less the same. Now if I decide to bring my child up traditionally, I know in my mind that its the best decision. But my neighbour sends his child for computer classes. What chance has my child got with farming and hunting in today’s world? When he grows up won’t he curse me for not educating him like the others?”

He laughed. “In the old days if a woman had ten children, everyone looked at her with awe and said ‘That’s some strong woman, she’s borne ten children.’ Our children were our wealth. Now they would look with pity and say, ‘Devamme (My god)! ten children! Poor thing she must be some stupid ignorant woman.’ Earlier, our children, the stock of paddy, our cattle were the signs of wealth. Now it is only money.”

Chathi moved to rituals. “When someone dies we question the gods. For us gods and people are equal.” KCK added, “We don’t worship our gods. That is the difference. We ask their advice, their help. But we scream and curse them when someone is ill or dies.”

Kali and Badchi, two Bettakurumba women added to this. “It is our good fortune,” Badchi explained “that our gods live with us in our villages and among our people. So we don’t have to go to find them in any mosque, temple or church. Religion, the fuss about conversion, being Hindu, Muslim or Christian is difficult to understand. For us the gods are important not the religion.” […]

Source: Through Adivasi eyes by Mari and Stan Thekaekara, ADIVASI : JULY 16, 2000

Address : http://www.hindu.com/folio/fo0007/00070480.htm

Date Visited: Sun May 26 2013 23:17:06 GMT+0200 (CEST)

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

“[A] common perception of conversion, prevalent in India, is that all conversions take place only among deprived lower caste or tribal groups, which are considered more susceptible to allurement or coercion. The reality of upper caste conversions is ignored in this climate of cynicism.”– Dr. Ivy Imogene Hansdak in Pandita Ramabai Saraswati: the convert as ‘heretic’ | More about the effects of “casteism” >>

Adivasi communities traditionally depended on the forest for all their nutritional needs. They subsisted mainly on fruits, vegetables, tubers, fish, small game as well as the occasional crop they grew, predominantly coarse grains. However, as time passed and the nature of, as well as their access to, forests changed, their diet started becoming deficient. […]

This deficiency started manifesting in the form of rampant malnutrition, among adults and children alike, underweight babies as well as high maternal mortality [and] increased susceptibility to Tuberculosis among the Adivasis.

Blog post “Gardening their way to Good Health” by ACCORD – Action for Community Organisation, Rehabilitation and Development (Accordweb, 14 March 2017) | Backup file:

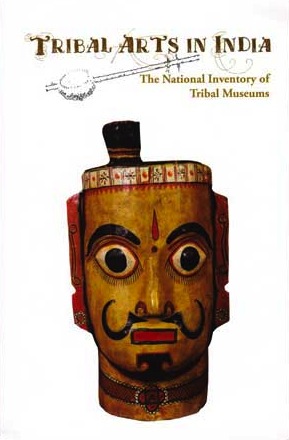

Tribal Arts in India | Worldcat.org >>

Free eBooks & Magazine by Bhasha Research and Publication Centre: Adivasi literature and languages >>

See also