Enlarge and learn more: Sound and vision blog | Backup: PDF-Repository >>

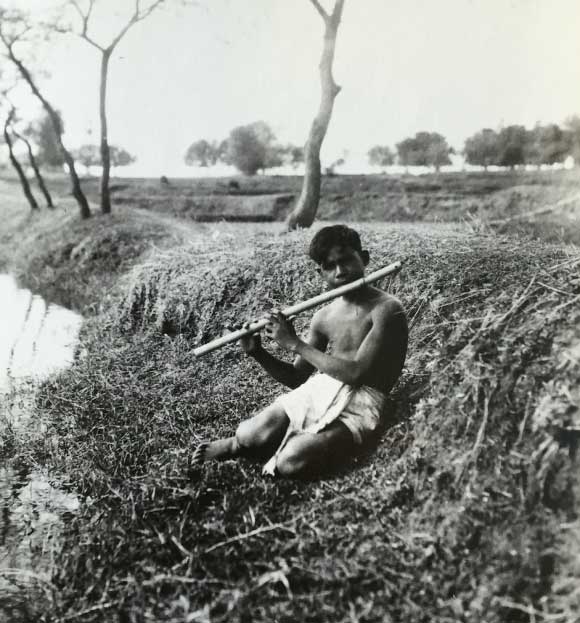

In Kairabani [Arnold Bake] photographed Santali pupils playing their instruments at the mission, but he seems to have been dissatisfied with the sober ambience of the premises. To also have a picture of a Santali musician in a natural environment, he probably arranged a photo with one of the musicians outside.

Source: “The Santals, Scandinavian missionaries, and salvage ethnomusicology: an encounter of three worlds”. Christian Poske, Sound and vision blog, British Library, 30.6.2020, accessed 21 February 2021

Tip: download the PhD thesis by Christian Poske titled “Continuity and Change: A Restudy of Arnold Adriaan Bake’s Research on the Devotional and Folk Music and Dance of Bengal 1925-1956”. SOAS University of London (2020).

https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34909/

View by Language (excerpt): Santali

Tip: search and listen to all of the available recordings on British Library Sounds >>

1. “Boeha dupulạr”: traditional Santali song; 2. “Coṭ cuṛa”: Santali Christian song; 3. Lagre song played on a large tiriya flute

“Boeha dupulạr”: traditional Santali song praising brotherly love, complete song performed by male vocalist (song also performed on C52/1648: 1, C52/2131: 4); 2. “Coṭ cuṛa”: Santali Christian song, based on a traditional Santali melody. The lyrics concern the right path to god, which is likened to a path leading through a forest in which satan dwells, posing dangers to those who walk carelessly; 3. Lagre song played on a large tiriya flute (also on C52/1647: 2, C52/2134: 2 & 3); 4. Ref tone. Reasonable quality recording.1. “Boeha dupulạr”: traditional Santali song; 2. Doń song; 3. Doń song

1. Lagre song; 2. Lagre song; 3. Sohrai song (beginning); 4. Sohrai song (end)

1. Mora karam song; 2. Song played on a large dhodro banam; 3. Song played on a large dhodro banam with male singing voices in the background

1. Sohrai song; 2. “Boge gupi do”: Santali church song; 3. Sohrai song

1. Sohrai song; 2. Bhinsar song; 3. Unidentified song, probably of the Lagre genre

1. Song played on a small tiriya flute; 2. The same song, performed by male vocalist accompanied unisono on a small tiriya flute; 3. “Otma lolo kạmru guru, serma setoṅ buạṅ guru”: incantation song

1. Unidentified song played on a small tiriya flute; 2. The same song performed by a male vocalist accompanied unisono on a small tiriya flute; 3. “Otma lolo kạmru guru, serma setoṅ buạṅ guru”: traditional Santali song, probably an incantation song, performed by male vocalist. Meaning of words: “kạmru guru” – teacher of charms, incantations and herbal medicine; “serma” – the sky; “setoṅ” – the rays of the sun; “buạṅ guru” – teacher of the buạṅ, a stringed musical instrument; 4. Ref. tone. Reasonable quality recording but with surface noise.

Updates by Christian Poske on 23 February 2021:

These are three Dasãe songs, which would traditionally be performed during the Dasãe daṛan(“September wandering”), a festive procession and rite of initiation for those learning the practices of Santali medicine from an ojha (“diviner, medicine man”). The updated documentation, given in my thesis, is therefore:

1. Dasãe song played on a small tiriya flute

2. Dasãe song (same as 1.), sung by male, with unisono accompaniment on a small tiriya flute

3. “O̱t ma lo̱lo̱, kạmru guru”: Dasāe song, sung by male

Bodding describes the Dasãe daṛan in detail in his Studies in Santal Medicine & Connected Folklore (1986 [1925-40]). In the book, he quotes the lyrics of a song that is almost identical to the third song on the cylinder:

O̱t ma lo̱lo̱, kạmru guru, serma setoṅ, buạṅ guru,

Yo̱ haere, cela do̱laṅ lalaoket’ko.

Sui sutạm gutukate se̱ne̱rre laṅ galaṅkako,

Reaṛ kaṇḍa, sitạ nala latarrelaṅ do̱ho̱kako.

That is,

The earth is hot, o Kạmru guru, the sky is fierce sunshine, o Buạṅ guru;

Alas, alas, we two have tantalised the disciples;

We two shall thread a needle and weave them on the rafter,

in a cool waterpot, below the Sita valley we two shall put them.

(Bodding, 1986, p.84)

Bake referred to the church song ‘Boge gupi do’ (‘The Good Shepherd’) that had been composed by the Norwegian missionary Lars Olsen Skrefsrud (1840-1910) [who] settled in India to make sustained efforts to convert the Santals from animist belief to Christianity [and] introduced a romanisation system providing the language with the first standard script that is still used by converts today, with minor amendments made by Bodding.

Source: “The Santals, Scandinavian missionaries, and salvage ethnomusicology: an encounter of three worlds”. Christian Poske, Sound and vision blog, British Library, 30.6.2020, accessed 21 February 2021

View by Location (excerpt): Kairabani (Jharkhand)

Tip: search and listen to all of the available recordings on British Library Sounds >>

1. “Boeha dupulạr”: traditional Santali song; 2. “Coṭ cuṛa”: Santali Christian song; 3. Lagre song played on a large tiriya flute

1. “Boeha dupulạr”: traditional Santali song; 2. Doń song; 3. Doń song

1. Lagre song; 2. Lagre song; 3. Sohrai song (beginning); 4. Sohrai song (end)

1. Mora karam song; 2. Song played on a large dhodro banam; 3. Song played on a large dhodro banam with male singing voices in the background

1. Sohrai song; 2. “Boge gupi do”: Santali church song; 3. Sohrai song

1. Sohrai song; 2. Bhinsar song; 3. Unidentified song, probably of the Lagre genre

1. Song played on a small tiriya flute; 2. The same song, performed by male vocalist accompanied unisono on a small tiriya flute; 3. “Otma lolo kạmru guru, serma setoṅ buạṅ guru”: incantation song

Number of items in collection: 87

Recordings in this collection can be played by anyone.

Arnold Adriaan Bake’s [1899-1963] collection of recordings from South Asia have been a great resource for many academics across several disciplines. The British Library is actively engaged with a number of international academics and communities who are working with wax cylinder recordings from the Arnold Adriaan Bake archive to enhance the documentation for these recordings. They are therefore being released in regional batches as research progresses.

Bake was a Dutch ethnomusicologist noted asa primary pioneer of the discipline and one of the foremost international academic experts on South Asian music. His recordings on wax cylinder, tefi-band, reel-to-reel tape and film from successive field trips, were made throughout South Asia with principle studies in Nepal, India and Sri Lanka, in 1925-29, 1931-34, 1937-46 and 1955-6.

Bake’s recordings document religious music found throughout South Asia, where he recorded festivals, weddings, funerals, religious practices and recitations. In addition Bake documented folk music and dance, including the stick dances and hobby horse customs which appear in European traditions and a thoroughly comprehensive study of the vocal and instrumental music of Nepal.

Source: Arnold Adriaan Bake South Asian Music Collection, British Library Sounds

URL: https://blogs.bl.uk/sound-and-vision/2020/06/the-santals-scandinavian-missionaries-and-salvage-ethnomusicology-an-encounter-of-three-worlds.html

Date visited: 6 November 2024

The Santals, Scandinavian missionaries, and salvage ethnomusicology: an encounter of three worlds

Since 2015, Christian Poske has conducted his PhD research on the Bengal recordings of the Arnold Bake Collection. A Collaborative Doctoral Scholarship from the Arts and Humanities Research Council UK, situated his PhD within two institutions: the British Library Sound Archive and SOAS, University of London. He conducted his fieldwork in Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Bangladesh from April to October 2017, revisiting the locations of Arnold Bake’s fieldwork. Christian’s fieldwork investigated the aims and methods of Bake’s research in the early 1930s and studied the continuity and change in the devotional and folk music and dance documented by Bake. Christian is completing his PhD in Music this year at SOAS and in addition to his research has been engaged as a cataloguer for the Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project. He currently works as Bengali Cataloguer at the Department of Asian and African Collections at the British Library. […]

The restudy of historical sound recordings often gives unexpected results. During my research on the cylinder recordings of the Dutch musicologist Arnold Bake (1899-1963) at the British Library Sound Archive, I came across a number of sparsely documented recordings made at a Christian mission for the Santals, a South Asian aboriginal people centred in the Indian state of Jharkhand today. When I [Christian Poske] conducted my fieldwork in 2017, I found out that one of the church songs recorded by Bake is still popular among converts in the region.

[Quoting Arnold Bake]

‘Recently, I had the opportunity to start recording Santal music… To really get in touch with the Santals, I have turned to the currently most important authority in this field, Dr Bodding… However, he is a missionary, and as he helped me along, we arrived at a huge boarding school for Santals. But it looks worse than it is. The mission has the policy to change as little as possible. Language, music and customs are, if anyhow possible, retained. All melodies used in the church are pure Santal melodies, although the words were made Christian… The music as such is quite unlike Hindu music, and their whole musical sense is very different. They love polyphony a lot when they get to hear it. I have recorded a sample (which hardly has any scientific value) how the Santal singing master of the school edited a song with four voices without actually ever having a European education, he does not speak a word of English, for example. The boys sing it with passion, which you could never expect from the Hindus…’

(Arnold Bake, letter to Erich M. v. Hornbostel, 15.4.1931, Berlin Phonogram Archive)With these words, Bake explained his fieldwork at the Kairabani mission to Erich M. v. Hornbostel (1877-1935), the director of the Berlin Phonogram Archive. The Norwegian missionary Paul Olaf Bodding (1865-1938) of the Santal Mission of the Northern Churches had arranged Bake’s visit to Kairabani. […]

Source: “The Santals, Scandinavian missionaries, and salvage ethnomusicology: an encounter of three worlds” (courtesy Christian Poske by email)

URL: https://blogs.bl.uk/sound-and-vision/2020/06/the-santals-scandinavian-missionaries-and-salvage-ethnomusicology-an-encounter-of-three-worlds.html

Date visited: 6 November 2024

Unlocking our Sound Heritage is a UK-wide project that will help save the nation’s sounds and open them up to everyone. […]

The Unlocking Our Sound Heritage project – part of the Save our Sounds programme – aims to preserve and provide access to thousands of the UK’s rare and unique sound recordings: not just those in our collections but also key items from partner collections across the UK.

Source: Unlocking Our Sound Heritage

URL: https://www.bl.uk/projects/unlocking-our-sound-heritage?_ga=2.195804588.1297834387.1613940073-1904369641.1613726698

Date visited: 21 February 2021

Photo © Ludwig Pesch

Learn more about a wide range of issues

including Education and literacy, Health and nutrition & Ethnobotany >>

UNESCO World Heritage Centre | Backup: PDF-Repository >>

Santali is one of India’s many Adivasi languages. Today, seven different alphabets are used to write in it. Some argue that this great variety does not help the community’s development. | Read the full article by Boro Baski (3,3 MB) | Backup: PDF-Repository >>

Among South Asian Adivasis, we are the largest homogenous group. More than 10 million people belong to Santal tribes in India’s eastern states as well as in Bangladesh and Nepal. Our tribes are outside the Hindu caste system and have been marginalised historically.

Santali, for example, has survived and evolved over the millennia in oral tradition. It is an Austro-Asiatic language that is related to Vietnamese and Khmer, but not to the Indo-European languages prevalent in our part of South Asia.

In the 1890s, Christian missionaries found it helpful to write in Santali. They used Roman (Latin) letters. This alphabet, of course, has been used in many parts of Europe since the days of the Roman Empire.

Related posts >>

Education began to spread among Santals, and was not only driven by Christian missionaries. Typically, people opted for the scripts that were predominant in the region. Where most people speak Bengali, Santals used the Bengali alphabet. Where Hindi or Nepali are more common, they opted for Devanagari, which is related to, but differs from the Bengali alphabet. Where Oriya is the lingua franca, however, that language’s script was chosen, which is entirely different.

The sad truth is that Santali language and literature started to develop in six different scripts. To some extent, those alphabets were modified to better suit our language, but none of them accurately reflects Santali phonemes. The more depressing problem, however, is that Santal writing in different alphabets does very little to unite our community across the regions. It neither helps us communicate among one another nor does it foster a stronger sense of self-confidence. […]

In West Bengal, most Santal children attend state schools where Bengali is the language of instruction. In the neighbouring states, other languages are prevalent. At the same time, Latin letters are still in use as well, not least because some of the books prepared early on by the missionaries are still in print. They are indeed very useful.

Things have become even more complicated in the past two decades because government agencies started to approve a seventh script. It is called Ol-chiki and was designed to more accurately represent Santali phonemes. Since the turn of the millennium, state institutions have been promoting this innovative alphabet consistently, and they now consider it the only legitimate way to write in Santali. […]

We want our young generation to be rooted in our specific culture and to have good opportunities to take their fate into their own hands. Using our language is essential. What alphabet we use in school, matters less. We tell our students about Ol-chiki – encouraging, but not forcing them to learn it.

Source: “Divided by scripts” by Boro Baski (D+C Development and Cooperation, e-Paper April 2021)

URL: https://www.dandc.eu/sites/default/files/pdf_files/dc_2021-04.pdf

Date visited: 7 April 2021

For decades, the Ol-chiki alphabet, which was invented to represent the Santali language, was largely irrelevant. That changed in the late 1970s.| Read the full article (3,3 MB) >>

The script had been developed in 1925 by Raghunath Murmu, an Adivasi intellectual. He wanted it to accurately represent the pronunciation of the language used by Santal tribe. […]

In 2004, Santali became one of India’s 22 official languages. No other Adivasi language has been granted that status. There now even is a Santali/Ol-chiki Wikipedia. [However] some Santals disagree with how the government is promoting Ol-chiki. They argue that other scripts are at least as useful, especially as they have a history of Santali literature. They consider Santali writing in any script to be valid. However, authors who do not opt for Ol-chiki are not even considered for the Government of India’s prestigious literary Santali Sahitya Akademi Award. The scenario is not entirely bleak however. As more teachers are trained to teach in Santali and more textbooks with Ol-chiki writing appear, educational results will improve. Moreover, there is scope for publishing the same Santali text in more than one script.

Source: “The pros and cons of Ol-chiki” by Boro Baski (D+C Development and Cooperation, e-Paper April 2021):

URL: https://www.dandc.eu/sites/default/files/pdf_files/dc_2021-04.pdf

Date visited: 7 April 2021

Two tribal villages in Bengal revive the Santali language

By Nandini Nair, OPEN Magazine, 13 January 2017 | To view more photos and read the full article, click here >>

PADA MURMU IS the kind of teacher any young child would be fortunate to have. Her eyes dance, her hands talk and her laughter soars as she attempts to engage every four-year-old in front of her. Seated under the sky which serves as a roof, and on gunny sacks that double up as chairs, these children are learning the Bengali alphabet. While most of the dozen-odd kids repeat after her, a few lose focus and play with the mud, drawing patterns and dropping pebbles. But even a casual observer will notice that this is an engrossed classroom. The students read the Bengali alphabet cards held out by Pada and recite ditties that she has taught them. This might seem par for the course in many schools, but here in Ghosaldanga, it is exceptional. Located around 170 km from Kolkata, just beyond the Kopai River, this is a rare Santali school. While any rickshaw waala from Santiniketan will tell you facts and fables about the connection between the Kopai and the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali is an alien language for these Santali students. And for native Bengali speakers, Santali is terra incognita.

Close to six million people in India speak Santali (2001 Census). It is spoken in Bihar’s Bhagalpur and Munger districts; Jharkhand’s Manbhum and Hazaribagh districts; Odisha’s Balasore district; West Bengal’s Birbhum and Bankura districts; and in parts of Assam, Mizoram, and Tripura. It is one of the few languages that is not particular to a single state, as Santali and its dialects (Karmali, Kamari-Santali, Lohari-Santali, Manjhi and Paharia) can be heard across the Chota Nagpur plateau. Interestingly, no one script is used for Santali. The Latin script is used in Bangladesh; Oriya script is used in parts of Odisha; the Ol Chiki script is used in certain pockets; and the Bengali script is used in Bengal. Santalis represent more than half (51.8 per cent) of the total Scheduled Tribe population of West Bengal. In the state only 40 per cent of Santals are literate (57 per cent of men; and a mere 27 per cent of women). These dry facts illustrate that while Santali is spoken by millions of people across eastern parts of India, its speakers remain outside the realm of letters, highlighting the importance of teachers like Pada. […]

For the students at Rolf Schoembs Vidyashram (RSV, locally also called the Ashram School), this non-formal Santal day school can make the difference between dropping out and flourishing. […]

The Ghosaldanga Adivasi Seva Sangha (GASS) that works with the tribal population of two Santal villages (namely Goshaldanga and Bishnubati) uses education as a tool to merge and stand out. GASS, along with the Bishnubati Adivasi Marshal Sangha, has been working in these two Santal villages for close to three decades. When they began, each village had only one student who had completed the madhyamik (secondary) examination. They were Boro Baski in Bishnubati village (who now runs the Ashram School) and Sona Murmu (the first student of the Ashram School and secretary of GASS). The efforts of Sona Murmu and Boro Baski have slowly changed the education system of these two villages, which have a combined population of less than 1,000 people.

The story of RSV is itself an example of serendipity and perseverance. […] By learning Bengali (the state language) through Santali (their mother tongue), the students of Ashram School carve a path to their future while preserving their past. Knowledge of Bengali will help them find employment, while the wisdom of Santali will keep them rooted. Boro Baski, who has translated Rabindranath Tagore’s Bengali play Raktakarabi into Santali and has composed several of the rhymes, says, “In Bengali schools, students learn only about Tagore and Gandhi. Not our own story. They are learning only how to become non-Santali. They learn that their future lies in the mainstream. In mainstream culture, there is no space to learn about their own cultures. But if they were to learn the Ol Chiki script, where will they go from here? That is why we teach them Bengali through Santali.”

Boro Baski, who studied at a missionary school and later at Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan, knows all too well the dangers of losing one’s language. While he was punished in school for speaking in Santali, today he is the most educated person in his village. At the Indian Language Festival Samanvay 2016, held in Delhi, he said, “For the Santalis, the survival of our language means the survival of our culture.” […]

In Bengali schools, students learn only about Tagore and Gandhi. Not our own story. They are learning only how to become non-Santali.

The two-pronged approach ensures that students at Ashram School-whether it is Jagdish who lives 5 km away, or Kolpi and Robina whose homes are closer-become bilingual, and thus independent. Sculpture and painting are part of the curriculum, as are dance and music. Santal students learn about their own history such as the Santal rebellion of 1855 against the British and the zamindari system; and their own freedom fighters such as Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu. The students even learn the English alphabet through song. They are taught ‘a’ looks like a pretty girl, while ‘b’ is a ladle to pour oil and ‘c’ is an open mouth. The alphabet book for the 80-odd students is bilingual, with every Santali word written alongside its Bengali counterpart, dadu (grandfather) is explained in Santali as gadam baba, and naach (dance) can be found cheek- to-jowl with the Santali enech. […]

Pada, the 22-year-old teacher, and a former student of RSV, attests to that. Speaking fluent Bengali she says, “Everything I knew, poetry, music, games, it was all in Santali. This school gave me a sense of community and I hope my students get to feel the same.” As a teacher, she believes that by learning Bengali through Santali, these students are able to find moments of co-relation.

Kalidasi Mardi, another teacher at the school, who also studied from KG to Class IV at RSV, echoes Pada’s sentiments. She is the first person in her family to be educated; today, she is a graduate of Visva-Bharati University. […] “The biggest problem is illiteracy. If there is one thing I want to see is that the future generations do not suffer like my parents did.“

Even while Pada acknowledges that it is essential that the Adivasi children learn the dominant language, she also asserts, “Bengali and Santali can’t really meet.” Why? With rehearsed ease, she explains, “When I teach my students, I try to stress that we need to remember that the central ideas about Santali culture is dance, music and poetry. There is no way Bengali dance and music can compare to Santali. We have a song for every situation. We feel money takes away from the enjoyment of life. But to earn a livelihood, people have to learn other languages.”

Pada’s answer, which panders to all the classical notions of ‘tribal’, can seem cookie-cutter and even cliché. But in this school and in these villages, one can trace the truth behind her sentiments. Bishnubati village, around 5 km from the school, is a place of delicate beauty. Walking through, it is easy to idealise, even exoticise, the settlement. The harvest has just been completed, the toil of the year lies piled in heaps. The paths are swept clean and no open drains can be seen. With the festival season around the corner, the huts are awash in a new coat of mud, and intricate painted flowers creep up the doorway. Even frescoes span a few of the houses in the main lane. Sanyasi Lohar, artist and teacher at RSV, rallied together a few of the villagers to create these panels of art that depict local festivals and scenes from daily life.

Here in Bishnubati, the conversations of Satyajit Ray’s last film Agantuk (The Guest) come to life. In the movie, the mysterious guest (played by Utpal Dutt) , claiming to be an anthropologist, says he has spent numerous years with the Adivasis of the country, be it Kols, Bhils, Nagas or Santals. In a heated exchange with a lawyer friend, the Guest says that living with tribals he has found that technology is not only a matter of science exploration, rather it is about hunting, weaving, farming and building a hut. When asked about the ‘taboos’ of tribal life, such as witchcraft and shamans, he says the Adivasi doctor with his knowledge of medicinal properties, saved his life. He retorts with defiance, “My biggest regret is that I am not a tribal.”

The debate about whether tribals should be kept separate or should be ‘assimilated’ and ‘mainstreamed’ dates back to the creation of the Indian state. At that time, Jawaharlal Nehru and the Government took the position that they should be allowed their isolation. But as GN Devy, author, professor, linguist and founder of Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh, Gujarat, said at a talk in 2013 titled ‘Why do the Adivasis want to Speak’, “Nobody asked the tribal does he or she want to be left alone, or assimilated.”

In early December, when Bengalis were just pulling out their monkey caps and digging into nolen gur, a seminar was held in Ghosaldanga village about the role of a community museum and its role in the education and development of Santals. The speakers at the event included Sushanta Dattagupta (former Vice-Chancellor of Visva-Bharati) and Kakali Chakraborty (Deputy Director, ASI). The conversations pivoted around questions of modernity and tradition, preservation and dynamism.

The Museum of Santal Culture in Bishnubati itself is a place of good intentions but hapless execution. It wears a new coat of white paint, but within its walls, the items (musical instruments, traps and nets, ornaments) lie listless and reveal no stories. Here one can see the dangers of ‘museumifying’ a culture; it moves from a pulsing living entity to a fossil behind glass. But the question arises: how is one to capture the essence of an oral culture, where memories have not been written down?

The answer is to be found back at the school. It is the end of the school day, the students pack their bags and head out to the world outside. Talking about her students and own experience at RSV, Kalidasi Mardi says, “The school has given me the ability to talk-that is the biggest thing.” The efforts of those like Boro Baski ensure that Santals are given a voice to tell their own stories.

Source: Santali: Talking Time | OPEN Magazine

Address: https://openthemagazine.com/features/dispatch/santali-talking-time/

Date Visited: Fri Jan 20 2017 09:56:47 GMT+0100 (CET)

[Bold typeface added above for emphasis]

Dr. Boro Baski works for the community-based organisation Ghosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha in West Bengal. The NGO is supported by the German NGO Freundeskreis Ghosaldanga und Bishnubati. He was the first person from his village to go to college as well as the first to earn a PhD (in social work) at Viswa-Bharati. This university was founded by Rabindranath Tagore to foster integrated rural development with respect for cultural diversity. The cooperation he inspired helps local communities to improve agriculture, economical and environmental conditions locally, besides facilitating education and health care based on modern science.

He authored Santali translations of two major works by Rabindranath Tagore, the essay “Vidyasagar-Charit” and the drama Raktakarabi (English “Red Oleanders”), jointly published by the Asiatic Society & Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) in 2020.

Other posts contributed by Dr. Boro Baski >>

Ghosaldanga Bishnubati Adibasi Trust

Registration under Trust Registration Act 1982

P.O. Sattore, Dist. Birbhum

West Bengal-731 236

India

For inquiries on Santal cultural and educational programs, please contact:

Mob. 094323 57160

Learn more about the status and spread of Santali in different regions of India: Clarifications by Dr. Ivy Imogene Hansdak >>

Find up-to-date information provided by, for and about Indian authors, researchers, officials, and educators

List of web portals covered by the present Custom search engine

Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) – www.atree.org

Freedom United – www.freedomunited.org

Government of India (all websites ending on “.gov.in”)

Kalpavriksh Environmental Action Group – https://kalpavriksh.org

Shodhganga (a reservoir of Indian theses) – https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in

Survival International – www.survivalinternational.org

UCLA Digital Library – https://digital.library.ucla.edu

Unesco – https://en.unesco.org

Unesco digital library – https://unesdoc.unesco.org

Unicef – www.unicef.org

United Nations – www.un.org/en

Video Volunteers – www.videovolunteers.org

WorldCat (“the world’s largest library catalog, helping you find library materials online”) – https://worldcat.org

To search Indian periodicals, magazines, web portals and other sources safely, click here. To find publishing details for Shodhganga’s PhD search results, click here >>

Search tips

Combine the name of any particular state, language or region with that of any tribal (Adivasi) community.

Add keywords of special interest (music, poetry, dance just as health, sacred grove and biodiversity); learn about the rights of Scheduled Tribes such as the “Forest Rights Act” (FRA); and the United Nations “Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples”, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”, “women’s rights”, or “children’s right to education”.

Ask a question that includes “tribal” or “Adivasi”, for instance: “Adivasi way of life better?” (or “tribal way of life worse?”)

Specify any particular issue or news item (biodiversity, bonded labour and human trafficking, climate change, ecology, economic development, ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, global warming, hunter-gatherers in a particular region or state, prevention of rural poverty, water access).

For official figures include “scheduled tribe ST” along with a union state or region: e.g. “Chhattisgarh ST community”, “Himalayan tribe”, “Scheduled tribe Tamil Nadu census”, “ST Kerala census”, “Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group Jharkhand”, “PVTG Rajasthan”, “Adivasi ST Kerala”, “Adibasi ST West Bengal” etc.

In case the Google Custom Search window is not displayed here try the following: (1) toggle between “Reader” and regular viewing; (2) in your browser’s Security settings select “Enable JavaScript” | More tips >>

Note: hyperlinks and quotes are meant for fact-checking and information purposes only | Disclaimer >>

Some clarifications on caste-related issues by reputed scholars >>