Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was the first public figure to highlight the value of his country’s tribal cultural heritage. He created an environment that accounts for the fact that Adivasi culture has long exerted a “profound influence on modern Indian art“. The same can be said about the inspiration derived by flute player Pannalal Ghosh, a pioneer in the field of Indian classical music as we know it today.

Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first Prime Minister, 1889-1964) discouraged the imposition of interventionist policies on tribal communities: he would not agree to creating a mere “second-rate copy of ourselves”.

Photo © Indian Express

While the development of modern Community facilities and educational institutions gathers momentum, Tribal elders continue to be revered in several parts of the country.

Photo © Ludwig Pesch

Learn more about the

Toda community, the Nilgiri Biosphere where the live, other elders,

the cultural identity communities have cherished for centuries, and this

in spite of the colonial legacy still affecting their members >>

The same can be said of the elevated status assigned to Women in many tribal communities:

“If women are empowered, there is more development in society” – Droupadi Murmu

Find this and other speeches by the 15th President of India >>

“Tribal communities are a standing example of how women play a major role in preservation of eco historic cultural heritage in India.” – Mari Marcel Thekaekara (writer and Co-Founder of ACCORD-Nilgiris).

Going by personal experience, Abhay Bang – an award-winning doctor and social activist from Gadchiroli – asserts that “there is no social bias against women in tribal communities such as there exists among the middle castes, especially landed ones: “Women can ask for a divorce, and in many communities, money is paid to the girl’s family at the time of marriage.” Yet negative stereotypes and cultural racism continue to form the backdrop to the discrimination and humiliation of Adivasis in general, and women in particular:

(scene in Kamla based on Vijay Tendulkar’s 1981 play)

Learn more about Accountability, Media portrayal, the stereotypical portrayal of tribal Women and Rural poverty >>

See also Aranyer Din Ratri (“Days and Nights in the Forest”) >>

In other words, “tribal men and women mix freely, but with respect for each other [but] caste Hindu society in India is so convinced of its own superiority that it never stops to consider the nature of social organisation among tribal people. In fact it is one of the signs of the ‘educated’ barbarian of today that he cannot appreciate the qualities of people in any way different from himself – in looks or clothes, customs or rituals.” – Guest Column in India Today >>

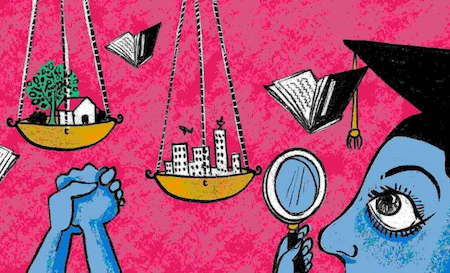

Some scholars analyse these developments with modern developments in mind, like “privatisation of enterprises and education [that] strengthened the importance of caste ties, as selection to posts and educational institutions is less based on merit through examinations, and increasingly on social contact as also on corruption.” Adverse inclusion of this kind is, obviously, rooted older practices: “Casteism is the investment in keeping the hierarchy as it is in order to maintain your own ranking, advantage, privilege, or to elevate yourself above others or keep others beneath you.”

Historian B.G. Gokhale refers to ancient texts when describing the multiple challenges faced by India’s indigenous communities to the present day: “The Aryans describe their enemies as dark in complexion […] named Dāsas, Asuras, Panis and Kīkatas. The Aryan invaders finally triumphed over the non-Aryans, many of whom were killed, enslaved or driven further inland. In this land, which the Aryans conquered from their enemies, were founded the early Aryan settlements.”

The ubiquitousness of the problems in terms of socio-economic development have kindled a sense of urgency. After all, “it’s a long road to freedom!” (Stan Swamy, the late sociologist and activist for Adivasi rights, remembered by the Indian Social Institute). The key for any tangible change is, of course, better education. During an award-ceremony, former President of India, Sri Pranab Mukherjee defined the responsability of educators as follows:

“Education has to liberate a person from narrow world view and the boundaries of caste, community, race and gender. Teachers have been entrusted with the responsibility of moulding the young minds to understand the world and make it better.”

The validity of this approach has already proven by several schools, each developing its own methodology and always in tune with local needs; for instance by way of incorporating “the forests and the Adivasi way of life” in Tamil Nadu: “The tribals had been led to believe that they were ‘uneducatable’, but when they saw the few tribal children in our school flourishing, they were convinced that it was the system and not the children at fault.” (B. Ramdas)

“The forest in Shanthi Teacher’s classroom” >>

- Continue the guided tour – Part 4 >>

- Start the guided tour (Part 1)